|

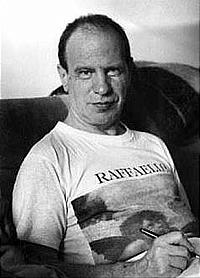

| Together at last fall's poetry biennale were, from left to right, Arion editor alexei Alyokhin, Moscow City Duma official Yevgeny Bunimovich and Vavilon founder Dmitry Kuzmin.

|

The main obstacle to putting together this year's celebration of International Poetry Day was a matter of logistics. Not the usual kind of logistics, since Moscow's lively literary scene ensured organizer Yevgeny Bunimovich both fail-safe venues and a devoted set of listeners. No -- here, the challenge lay in getting all of the festival participants to tolerate being in the same room for more than five minutes.

"It was relatively difficult to bring these events together," said Bunimovich, a poet who answers for cultural issues at the Moscow City Duma and has coordinated Moscow's International Poetry Day festival since it was established in 1999. "If the first year we simply held an event marking International Poetry Day, the next year we started devoting it to young poets. This is natural since they are usually the pulse of the literary scene. But as it turned out, certain young poets won't take the stage together with certain other young poets."

International Poetry Day has been celebrated worldwide since its establishment five years ago by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The idea behind the project, UNESCO proclaimed in 1999, was to bring new poets to the public's attention, as well as to encourage the efforts of small poetry publishers. Drawing on the common association of poetry with renewal, UNESCO set International Poetry Day for the first day of spring, brushing over the fact that the United Nations had already dedicated March 21 to the elimination of racial discrimination.

Under Bunimovich's leadership, Moscow poets held their first celebration of International Poetry Day that very same year. But as time went on, the rifts between the literary groups forced Bunimovich to organize two parallel literary events devoted to young poets: a traditional celebration under the auspices of established poetry journal Arion and a more avant-garde festival run by the literary club OGI.

But in a sign that times are changing, last year's Third International Poetry Biennale, which Bunimovich also organized, featured a grudging semblance of cooperation, and more interaction is expected in this week's activities. "The poetry landscape has become much more complicated and can't be limited to those two groups of young poets," Bunimovich said. "Thank God, all of the groups understand that the general structure, the general idea of keeping the poetry scene alive, is most important, so they're willing to participate in a single lineup. They won't take the stage together, but thank God they're willing to tie together their separate events."

To bring these poetry groups together, Bunimovich has extended International Poetry Day to a poetry week, with 14 different concerts, video-projects, discussions and poetry readings running through Friday at literary clubs around the city. "As always in Russia, one day is not enough," laughed Nadezhda Vishnyakova, director of the Foundation of Creative Projects, the non-profit cultural organization of which Bunimovich is president.

|

|

www.vavilon.ru

Konstantin Kedrov will conduct two events for International Poetry Day.

|

From the more established side of the literary scene come two evenings at Project OGI featuring poets Lev Rubinstein and Dmitry Prigov, poetry innovators of the 1970s, as well as the 10th-anniversary celebration of Russia's first journal exclusively devoted to poetry, Arion. Poet Konstantin Kedrov will curate two events on Sunday together with his poetic group, the Voluntary Society for the Protection of Dragonflies, while a more experimental approach will be heard from the Vavilon Union of Young Poets. Vavilon has served as the organizational hub for Moscow's experimental scene since its founding by poet Dmitry Kuzmin in 1989, putting out some 30 issues of a youth-centered journal, diligently coordinating poetry events on its website and representing young Russian poets at festivals around the globe.

This Saturday and Sunday, however, will mark the end of Vavilon's existence -- for the simple reason, Kuzmin said, that the group's contributors are no longer young. "Now, all of the writers who founded the project are well over 30. So we decided to close the project down, because a new generation of young poets has already grown up. Those who are now 20 years old are already a different generation."

Yet even as he comes to terms with his own aging process, Kuzmin, still quite youthful at 35, takes no pains to hide his dissatisfaction with traditional approaches. In his opinion, most of the Russian literary establishment is mired in Soviet aesthetics that dictate that art should be simple and easy to understand. "If you take a look at the literary magazines, you'll see that they're always publishing articles on the subject. Someone's always writing some essay about how the real value of a literary work is its accessibility to a wider public," he said.

Even when literary journals do publish experimental work, Kuzmin argued, they do it for "Soviet" reasons. "Most of these publications inherited a Soviet aversion to taking a strong position. In Soviet times, there was no conception that a journal had to develop some particular character. There was never any of that. So they're also afraid to give flat-out 'no's to any strong tendency in contemporary literature."

Thanks to festival organizer Bunimovich's intervention, though, outspoken avant-gardists like Vavilon will take the stage this week with more traditionally minded journals like Arion. On Sunday evening at Sad, Vavilon will release its final literary journal and an anthology called "Nine Dimensions" that clocks in at over 400 pages of work by poets who came to age after the Soviet Union fell. And on Saturday evening at nightclub B2, Kuzmin's group -- which Bunimovich credited with "raising a ruckus" throughout the 1990s -- will ceremonially hand over the baton to a group of younger poets.

But as to whether a new organization will actually coalesce to take Vavilon's place, Kuzmin is not so sure. In his opinion, there is less of a need for active youth coordination than there had been in the early 1990s, when the end of censorship released a glut of samizdat writing from the 1960s and 1970s, as well as works from the early part of the century that had been suppressed.

"All of this began to be printed at once, and it took so much of the attention of readers, critics and specialists that there was nothing left for writers making their debut," Kuzmin said. "That's why [Vavilon] got started -- not to publicize the society of young writers, but to help young writers find each other, find out what was happening, engage in dialogue, so that it wouldn't all get lost.

"Now, the situation is completely different," he went on, adding that his future plans include starting a journal that encourages experimental writing but does not stick exclusively to debut writers. "We lead a relatively normal literary life. And the interest of journals and critics in young writers is considerable."

If Kuzmin is right, then the beginning of the 21st century might eventually become known as the time when Russia's warring poetry circles finally learned to get along. From the manifesto-wielding experimentalists of the 1920s to the dissident contempt for Soviet propaganda that prevailed over the following decades, poetry politics have never been a joke. As far as Bunimovich is concerned, organizing festivals devoted to worldwide events such as International Poetry Day is one way to channel these same healthy tempers into a less vindictive literary scene.

"It's wonderful when they disagree on aesthetic terms," Bunimovich said. "But they have to overcome their personal differences. It seems to me that we live in one poetry space and will appear, no matter what, in the same anthology a hundred years from now."

Festivities for International Poetry Day run through Friday at various locations. For a detailed list of all events, call the Foundation of Creative Projects at 332-2533 or visit www.ftp-culture.ru.

See also:

the original at www.themoscowtimes.com

|